The game in question is 1999’s The Longest Journey.

I bought it in a box. I had to go to a special shop, and they only had three copies. It was some sort of weird European import.

Best Adventure Game?

How do we want to talk about this “adventure game?” Shall we shove it into the awkward “genre” meatgrinder and put a label on the resulting sausage? Do we call it a storygame? Do we remember it because of its mechanics (“classic point-and-click adventure,” in the year traditional Adventure Games just might have died?) Or the moments, the “choices,” the beats? The personal experience of threading the narrative? Or is it all about April and Crow? How about the world(s)-building? Or the infamous long and chatty dialog trees? Omigod, what even are games!?!

What was a game like The Longest Journey doing in 1999? That’s the year Sierra finally gave up on all those “-quest” games they’d so happily made for years. But narrative was flourishing! It was the year of genre-flexible games where story was paramount, for ex, System Shock 2, Alpha Centauri, and Planescape: Torment. But the old clicky-pointy-puzzle games? They had either failed to keep up, or else had tried to do too much. Gamers Like Me(tm) would still sign up for a novel’s worth of reading in choicey, dialog-heavy snippets. But we’d only read it if we could also have hit points and fireballs and weapons that break and horrors to be survived. (I knew this, even though I’d missed that other startling game from 1999, Silent Hill.)

Puzzling Evidence

LucasArts fans will tell you that adventure games closed up shop in 1998 after (the brilliant) Grim Fandango, and only really got going again when Telltale stopped making clicky puzzle games in 2012 and went all-in cinematic with The Walking Dead.

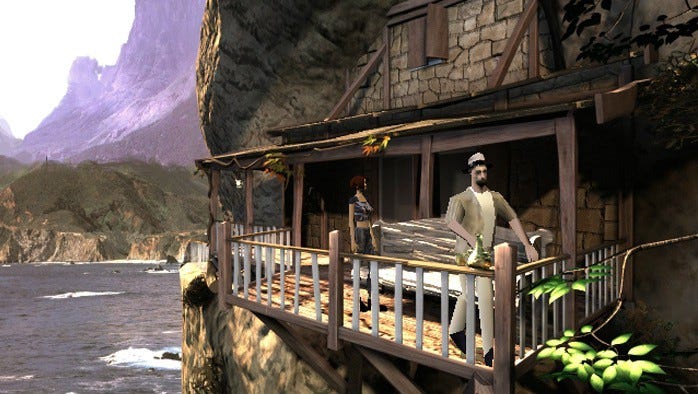

And yet. There was still this game, this goofy sprawling charming game. It starts with a frame tale, “tell me a story,” and then throws us into a the dreamworld of a young female protag who slips back and forth between a futuristic yet rundown semi-dystopia and a green world of odd fuzzy creatures and an all-consuming blob of Chaos. The pace is gentle, letting you pause as long as you like to admire the painted backgrounds and chat with your landlady — and trying to let the voice acting move you beyond the clunky 3D character models. It was concocted and written by a 20-something who didn’t know how it would end until he got there, filling in all the dialog in a few weeks of “writing at night until 3 or 4 in the morning”, handing off the results to voice actors. In other words, it was inspired, confused, limber, naïve, and delightfully vital — even as its structure and rules leaned heavily on what went before.

What did it do? What do these kind of games ever do: Exploration, Puzzles, Dialog and Characters, Plot, Setting…Both the Science and Fantasy worlds are beautiful to look at, and full of intriguing corners, systems, and mysteries. There are enough puzzles (of…varying quality) that it never feels like you’re clicking through a movie or visual novel. The game tries to not lose that agency of it being your story, not just a theme park ride. But it mostly achieves that through building affection for our protagonist. It’s easy to love art student heroine April Ryan, or it was for 20-something me, and the moments between her and the rest of the characters brought us into the split worlds of Stark and Arcadia just as much as the world-building and scenic vistas.Writer Ragnar Tornquist’s late nights translated into charming dialog with a dash of Whedon, alternately arch and warm. They Big Story delivers a satisfying conclusion, with enjoyable meanderings on the way. And it’s all a bit of a mess, but we always want to follow all the pieces and their connections back. We come back for the ancient dragons and The Balance and for mysterious underwater aliens, but also just as much for April and Crow’s easy camaraderie.

Years later, we see the tension about What’s In Charge Here. Do the mechanics serve the story? Or the other way around? Or do they just sort of awkwardly co-exist? Would you perform them, scratch your head over them, without the context of place and character? In the best games, we hope they mutually reinforce each other. In a time before the derisively-named “walking simulator” gave up on arbitrary puzzles, fusty minigames, and quick-time events, and in a time before every secret was a quick search away, where does this game hit its stride?

Without RPGs’ pat-on-the-head sense of reward for progression, the story, the interaction between the characters of The Longest Journey have to hold it all together, make it memorable and interesting. This is core Adventure Game territory. Halfway through Season One of Telltale’s The Walking Dead, we move from caring about immediate danger and supplies for survival to caring for the emotional health of the group. But do they transcend what’s possible from other games of other genres? (Let alone a book or a television show or a movie.)

Let’s Go Watch A Kite

I remember the first time I noticed the direction of in-game’s “cut scenes” —a moment of conflict on the docks of Nar Shadda in Knights of the Old Republic II: The Sith Lords. Oh! How long have they been doing this? I wondered, as it dawned on me that the gamemakers had very deliberately directed my gaze, and how carefully they had set the scene. I know; I’m slow. But today we have to ask — can cinematic chops sustain a game in the era of “Let’s Plays” and streaming? I’m old enough that it’s very hard for me to understand why someone would want to watch a YouTube video of someone else playing a game. And yet people surrender their player agency (my precious!) just to see another person walk through a series of cut scenes. You can argue that this phenomenon contributed to the demise of Telltale.

But what gives us this agency? How open can we make a gorgeous and fascinating setting? How well can a developer hide the rails and help us suspend our disbelief? How do we find that protagonist sweet spot with both a strong personality and room for our own investment and identification? What works? Movement in space — the sort of open-world exploration Telltale gave up on and left to RPGs? Or is it dialog trees? Very, very large dialog trees? Great voice acting which helps create memorable character interactions? (Are we talking about Torment now?)

Or is it the specific misdirection trick Telltale did so well, of leading us along a single track while telegraphing how important our every choice was. And they weren’t even lying: your choices might not steer a big branching Choose-Your-Own-Adventure plot, but they certainly defined what sort of person your character was and their relationships with others. What provides more agency: a world-state decision, or choosing the reasons behind the decision? Does “why” matter just as much or more than “what”? How much does a game benefit from this sort of explicit feeding of player headcanon? What memorable game experience is built from, as Alexis Kennedy terms them, reflective choices?

And even as The Longest Journey hews close to 80s and 90s adventure game gameplay conventions, even as it certainly has its Great Big Important Story to tell and exposition to deliver, it never fails to give us those special moments between April and the other characters. It gives us, as players, that intimate feeling of connection that games do so well. The puzzles often don’t do it any favors. The story remains mostly linear — few (one?) big causal choices are to be found. And yet, the experience…

The Longest Journey doesn’t play with genre expectations, or subvert our ideas of how mechanics alter our experience, or take self-aware steps to innovate out of its cohort’s cul-de-sac. It’s just a great slew of ideas and art and personalities and cultures and conflicts and transformation, all put together with love and serious regard and humor. And that’s why I love it back.

Further points of departure:

Comparisons with other female protagonists: Max Caulfield, Clementine, Fiona, Ms. Croft, Zoe Castillo in Dreamfall

Abstract characters versus characters with specific personalities: Dragon Age / Mass Effect vs. The Witcher.

Later TLJ games: Do they catch the same lightning in a bottle? Do their changes help or hinder?

Dadification vs. reactivity through NPCs